Difference between revisions of "BaBE - Bash By Examples"

imported>ThorstenStaerk |

m |

||

| (40 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

BaBE - Bash By Examples; Your significant Linux scripting tutorial;; | BaBE - Bash By Examples; Your significant Linux scripting tutorial;; | ||

| − | <pic src="http://www.linuxintro.org/images/Bash-scripting-mindmap.jpg" width=70% align=right caption=MindMap /> | + | <pic src="http://www.linuxintro.org/images/Bash-scripting-mindmap.jpg" width=70% align=right caption="MindMap of what you can learn about Linux scripting" /> |

= Hello world = | = Hello world = | ||

The easiest way to get your feet wet with a programming language is to start with a program that simply outputs a trivial text, the so-called hello-world-example. Here it is for bash: | The easiest way to get your feet wet with a programming language is to start with a program that simply outputs a trivial text, the so-called hello-world-example. Here it is for bash: | ||

* create a file named hello in your home directory with the following content: | * create a file named hello in your home directory with the following content: | ||

| − | + | #!/bin/bash | |

| − | + | echo "Hello, world!" | |

| − | * [[open a console]], | + | * [[open a console]], make the file executable: |

| − | |||

chmod +x hello | chmod +x hello | ||

* now you can execute your file like this: | * now you can execute your file like this: | ||

| − | + | ./hello | |

Hello, world! | Hello, world! | ||

* or like this: | * or like this: | ||

| − | + | bash hello | |

Hello, world! | Hello, world! | ||

You see - the output of your shell [[program]] is the same as if you had entered the commands into a console. | You see - the output of your shell [[program]] is the same as if you had entered the commands into a console. | ||

| Line 23: | Line 22: | ||

= calling commands = | = calling commands = | ||

In your shell script you can call every command that you can call when [[opening a console]]: | In your shell script you can call every command that you can call when [[opening a console]]: | ||

| − | |||

echo "This is a directory listing, latest modified files at the bottom:" | echo "This is a directory listing, latest modified files at the bottom:" | ||

ls -ltr | ls -ltr | ||

| Line 29: | Line 27: | ||

firefox | firefox | ||

echo "Continuing with the script" | echo "Continuing with the script" | ||

| − | |||

= variables = | = variables = | ||

| Line 37: | Line 34: | ||

read name | read name | ||

echo "hello $name" | echo "hello $name" | ||

| + | |||

You see that the name is stored in a variable $name. Note the quotation marks '''"''' around "hello $name". By using these you say that you want variables to be replaced by their content. If you were to use apostrophes, the name would not be printed, but $name instead. | You see that the name is stored in a variable $name. Note the quotation marks '''"''' around "hello $name". By using these you say that you want variables to be replaced by their content. If you were to use apostrophes, the name would not be printed, but $name instead. | ||

| Line 44: | Line 42: | ||

or | or | ||

echo "${name}" | echo "${name}" | ||

| − | So what is the sense of this? Imagine you want to | + | So what is the sense of this? Imagine you want to append a string, without any blank, to a variable: |

| − | |||

echo "if I add the syllable owa to your name it will be ${name}owa" | echo "if I add the syllable owa to your name it will be ${name}owa" | ||

| − | |||

== common mistakes == | == common mistakes == | ||

| Line 57: | Line 53: | ||

= parameters = | = parameters = | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | echo "Here are all parameters you called this script with: $@" | + | echo "Here are all parameters you called this script with: $@" |

| − | echo "Here is parameter 1: $1" | + | echo "Here is parameter 1: $1" |

| − | echo "Which parameter do you want to be shown? " | + | echo "Which parameter do you want to be shown? " |

| − | read number | + | read number |

| − | args=("$@") | + | args=("$@") |

| − | echo "${args[$number-1]}" | + | echo "${args[$number-1]}" |

| − | |||

= return codes = | = return codes = | ||

| Line 72: | Line 67: | ||

* delivering a return code | * delivering a return code | ||

The return code is 0 if everything worked well. You can query it for the most recent command using $?: | The return code is 0 if everything worked well. You can query it for the most recent command using $?: | ||

| − | |||

bootstick@bootstick:~$ echo "hello world"; echo $? | bootstick@bootstick:~$ echo "hello world"; echo $? | ||

hello world | hello world | ||

| Line 79: | Line 73: | ||

bash: /proc/cmdline: Permission denied | bash: /proc/cmdline: Permission denied | ||

1 | 1 | ||

| − | |||

In bash, true is 0 and false is any value but 0. There exist two commands, true and false that deliver true or false, respectively: | In bash, true is 0 and false is any value but 0. There exist two commands, true and false that deliver true or false, respectively: | ||

| Line 88: | Line 81: | ||

= line feeds = | = line feeds = | ||

| − | + | In bash you can use line feeds or semicolons to separate commands. For example: | |

| + | |||

read name | read name | ||

if [ $name = "Thorsten" ]; then echo "I know you"; fi | if [ $name = "Thorsten" ]; then echo "I know you"; fi | ||

| + | |||

Instead of a semicolon you can write a line feed like this: | Instead of a semicolon you can write a line feed like this: | ||

| + | |||

read name | read name | ||

if [ $name = "Thorsten" ] | if [ $name = "Thorsten" ] | ||

then echo "I know you" | then echo "I know you" | ||

fi | fi | ||

| − | + | ||

| + | |||

| + | So we could put everything into one line and separate the commands by semicolons: | ||

| + | |||

read name; if [ $name = "Thorsten" ]; then echo "I know you"; fi | read name; if [ $name = "Thorsten" ]; then echo "I know you"; fi | ||

| − | If you want to insert a line feed where you do not need one, e.g. to make the code better readable, | + | |

| + | |||

| + | If you want to insert a line feed where you do not need one, e.g. to make the code better readable, just put a backslash at the line's end to indicate it will continue: | ||

| + | |||

read \ | read \ | ||

name | name | ||

| Line 119: | Line 121: | ||

== piping == | == piping == | ||

[[Piping]] is a very elegant concept in the Linux world. It allows you to take one command's output and use it as input for the next command. Now you can divide tasks into smaller tasks. For example instead of having a program counting all files in a directory you use one program (ls) to ''list'' all files in a directory and one program (wc) to count the lines: | [[Piping]] is a very elegant concept in the Linux world. It allows you to take one command's output and use it as input for the next command. Now you can divide tasks into smaller tasks. For example instead of having a program counting all files in a directory you use one program (ls) to ''list'' all files in a directory and one program (wc) to count the lines: | ||

| − | + | ||

ls | wc -l | ls | wc -l | ||

| − | + | ||

You can also put the output into a variable, in this case $arch: | You can also put the output into a variable, in this case $arch: | ||

| − | + | ||

uname -m | while read arch; do echo "Your system is a $arch system."; done | uname -m | while read arch; do echo "Your system is a $arch system."; done | ||

| − | |||

== comparison == | == comparison == | ||

| Line 142: | Line 143: | ||

read name | read name | ||

if [ $name = "Thorsten" ]; then echo "I know you"; fi | if [ $name = "Thorsten" ]; then echo "I know you"; fi | ||

| + | |||

Now let's look closer at this, why does it work? Why is there a blank needed behind the [ sign? The answer is that [ is just an ordinary [[command]] in the shell. It delivers a return code for the expression that follows till the ] sign. To prove this we can write a script: | Now let's look closer at this, why does it work? Why is there a blank needed behind the [ sign? The answer is that [ is just an ordinary [[command]] in the shell. It delivers a return code for the expression that follows till the ] sign. To prove this we can write a script: | ||

| − | + | ||

if true; then echo "the command following if true is being executed"; fi | if true; then echo "the command following if true is being executed"; fi | ||

if false; then echo "this will not be shown"; fi | if false; then echo "this will not be shown"; fi | ||

| − | |||

== empty strings == | == empty strings == | ||

| Line 158: | Line 159: | ||

== arithmetic expressions == | == arithmetic expressions == | ||

You can compare integer numbers like this: | You can compare integer numbers like this: | ||

| + | |||

echo "what is your age? " | echo "what is your age? " | ||

read age | read age | ||

if (( $age >= 21 )); then echo "Let's talk about sex."; fi | if (( $age >= 21 )); then echo "Let's talk about sex."; fi | ||

| + | |||

However bash does not understand floating point numbers. To compare floating numbers you will use external programs such as bc: | However bash does not understand floating point numbers. To compare floating numbers you will use external programs such as bc: | ||

| − | + | ||

$ if [ $(echo "2.1<2.2"|bc) = 1 ]; then echo "correct"; else echo "wrong"; fi | $ if [ $(echo "2.1<2.2"|bc) = 1 ]; then echo "correct"; else echo "wrong"; fi | ||

correct | correct | ||

$ if [ $(echo "2.1>2.2"|bc) = 1 ]; then echo "correct"; else echo "wrong"; fi | $ if [ $(echo "2.1>2.2"|bc) = 1 ]; then echo "correct"; else echo "wrong"; fi | ||

wrong | wrong | ||

| − | |||

== not equal == | == not equal == | ||

To check if a variable is NOT equal to whatever, use !=: | To check if a variable is NOT equal to whatever, use !=: | ||

| − | + | ||

if [ "$LANG" != "C" ]; then echo "please set your system lanugage to C"; fi | if [ "$LANG" != "C" ]; then echo "please set your system lanugage to C"; fi | ||

| − | |||

== common mistakes == | == common mistakes == | ||

| Line 230: | Line 231: | ||

The following code checks if the file dblog.log exists. As long as this is not the case it tries to download it via ftp: | The following code checks if the file dblog.log exists. As long as this is not the case it tries to download it via ftp: | ||

| − | |||

while ! (test -e dblog.log); do | while ! (test -e dblog.log); do | ||

ftp -p ftp://user:password@server/tmp/dblog.log >/dev/null | ftp -p ftp://user:password@server/tmp/dblog.log >/dev/null | ||

| Line 236: | Line 236: | ||

sleep 1 | sleep 1 | ||

done | done | ||

| − | |||

== common mistakes == | == common mistakes == | ||

| Line 248: | Line 247: | ||

= forking a process = | = forking a process = | ||

You can build a process chain using parantheses. This is useful if you want to have two instruction streams being executed in parallel: | You can build a process chain using parantheses. This is useful if you want to have two instruction streams being executed in parallel: | ||

| − | (find -iname "helloworld.txt") & | + | (find -iname "helloworld.txt") & (sleep 5; echo "Timeout exceeded, killing process"; kill $!) |

| − | |||

= functions = | = functions = | ||

| Line 271: | Line 269: | ||

= react on CTRL_C = | = react on CTRL_C = | ||

The command trap allows you to trap CTRL_C keystrokes so your script will not be aborted | The command trap allows you to trap CTRL_C keystrokes so your script will not be aborted | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | trap shelltrap INT | + | #!/bin/bash |

| − | + | ||

| − | shelltrap() | + | trap shelltrap INT |

| − | { | + | |

| − | + | shelltrap() | |

| − | } | + | { |

| + | echo "You pressed CTRL_C, but I don't let you escape" | ||

| + | } | ||

| + | |||

| + | while true; do read line; done | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

;Note: You can still ''pause'' your script by pressing CTRL_Z, send it to the [[background]] and kill it there. To catch CTRL_Z, replace INT by TSTP in the above example. To get an overview of all signals that you might be able to trap, [[open a console]] and enter | ;Note: You can still ''pause'' your script by pressing CTRL_Z, send it to the [[background]] and kill it there. To catch CTRL_Z, replace INT by TSTP in the above example. To get an overview of all signals that you might be able to trap, [[open a console]] and enter | ||

| Line 291: | Line 289: | ||

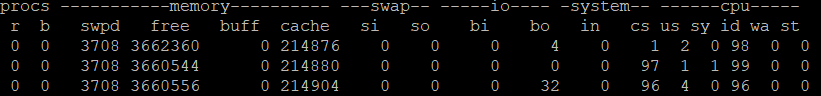

[[awk]] is a program that is installed on almost all Linux distributions. It is a good helper for text stream processing. It can extract columns from a text. Let's imagine you want to use the [[program]] [[vmstat]] to find out how high the CPU user load was. Here is the output from vmstat: | [[awk]] is a program that is installed on almost all Linux distributions. It is a good helper for text stream processing. It can extract columns from a text. Let's imagine you want to use the [[program]] [[vmstat]] to find out how high the CPU user load was. Here is the output from vmstat: | ||

| − | <pic src="http://www.linuxintro.org/images/vmstat.png" align=text width=100% caption=VmStat /> | + | <pic src="http://www.linuxintro.org/images/vmstat.png" align=text width=100% caption=VmStat /> |

We see the user load is in colum 13, and we only want to print this column. We do it with the following command: | We see the user load is in colum 13, and we only want to print this column. We do it with the following command: | ||

| Line 305: | Line 303: | ||

To store the CPU user load into a variable we use | To store the CPU user load into a variable we use | ||

load=$(vmstat 1 2 | tail -n 1 | awk '{print $13}') | load=$(vmstat 1 2 | tail -n 1 | awk '{print $13}') | ||

| + | |||

What happens here? First vmstat outputs some data in its first line. The data about CPU load can only be rubbish because it did not have any time to measure it. So we let it output 2 lines and wait 1 second between them ( => vmstat 1 2 ). From this command we only read the last line ( => tail -n 1 ). From this line we only print column 13 ( => awk '{print $13}' ). This output is stored into the variable $load ( => load=$(...) ). | What happens here? First vmstat outputs some data in its first line. The data about CPU load can only be rubbish because it did not have any time to measure it. So we let it output 2 lines and wait 1 second between them ( => vmstat 1 2 ). From this command we only read the last line ( => tail -n 1 ). From this line we only print column 13 ( => awk '{print $13}' ). This output is stored into the variable $load ( => load=$(...) ). | ||

== grep: search a string == | == grep: search a string == | ||

[[grep]] is a [[program]] that is installed on almost all Linux distributions. It is a good helper for text stream processing. It can extract lines that contain a string or match a [[regex]] pattern. Let's imagine you want all external links from www.linuxintro.org's main page: | [[grep]] is a [[program]] that is installed on almost all Linux distributions. It is a good helper for text stream processing. It can extract lines that contain a string or match a [[regex]] pattern. Let's imagine you want all external links from www.linuxintro.org's main page: | ||

| + | |||

wget -O linuxintro.txt http://www.linuxintro.org | wget -O linuxintro.txt http://www.linuxintro.org | ||

| − | grep "http:" linuxintro.txt | + | grep "http:" linuxintro.txt |

== sed: replace a string == | == sed: replace a string == | ||

| Line 323: | Line 323: | ||

* to replace protocol names for a given port (in this case 3200) in /etc/services: | * to replace protocol names for a given port (in this case 3200) in /etc/services: | ||

| + | |||

sed -ri "s/.{16}3200/sapdp00 3200/" /etc/services | sed -ri "s/.{16}3200/sapdp00 3200/" /etc/services | ||

| + | |||

* if you have an [[apache]] [[web server]] here's how you get the latest websites that have been requested: | * if you have an [[apache]] [[web server]] here's how you get the latest websites that have been requested: | ||

| − | cat /var/log/apache2/access_log | sed " | + | |

| + | cat /var/log/apache2/access_log | sed ";.*\(GET [^\"]*\).*;\1;" | ||

== tr: replace linebreaks == | == tr: replace linebreaks == | ||

[[sed]] is a [[program]] that is installed on almost all Linux distributions. It is a good helper for text stream processing. It can replace a character by another one, even over line breaks. | [[sed]] is a [[program]] that is installed on almost all Linux distributions. It is a good helper for text stream processing. It can replace a character by another one, even over line breaks. | ||

For example here is how you remove all empty lines from your processor information: | For example here is how you remove all empty lines from your processor information: | ||

| + | |||

# cat /proc/cpuinfo | while read a; do ar=$(echo -n $a|tr '\n' ';') | # cat /proc/cpuinfo | while read a; do ar=$(echo -n $a|tr '\n' ';') | ||

if [ "$ar" <> ";" ]; then echo "$ar"; fi; done | if [ "$ar" <> ";" ]; then echo "$ar"; fi; done | ||

| Line 335: | Line 339: | ||

== wc: count == | == wc: count == | ||

With the command wc you can count words, characters and lines. wc -l counts lines. For example to find out how many semicolons are in a line, use the following statement: | With the command wc you can count words, characters and lines. wc -l counts lines. For example to find out how many semicolons are in a line, use the following statement: | ||

| + | |||

while read line | while read line | ||

do echo "$line" | tr '\n' ' ' | sed "s/;/\n/g" | wc -l | do echo "$line" | tr '\n' ' ' | sed "s/;/\n/g" | wc -l | ||

done | done | ||

| + | |||

It lets you input a line of text, counts the semicolons in it and outputs the number. | It lets you input a line of text, counts the semicolons in it and outputs the number. | ||

| Line 355: | Line 361: | ||

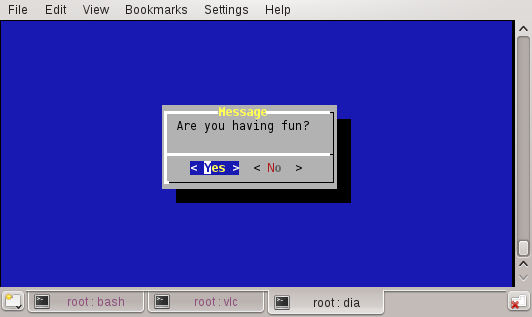

It will display this dialog: | It will display this dialog: | ||

| − | + | <pic src=http://www.linuxintro.org/images/Snapshot-dialog.png /> | |

This has been taken from http://www.linuxjournal.com/article/2807. Read there for more info. | This has been taken from http://www.linuxjournal.com/article/2807. Read there for more info. | ||

Latest revision as of 20:00, 24 March 2021

BaBE - Bash By Examples; Your significant Linux scripting tutorial;;

|

MindMap of what you can learn about Linux scripting |

Contents

- 1 Hello world

- 2 calling commands

- 3 variables

- 4 parameters

- 5 return codes

- 6 line feeds

- 7 storing a command's output

- 8 conditions

- 9 Redirections

- 10 filling files

- 11 loops

- 12 negations

- 13 sending a process to the background

- 14 forking a process

- 15 functions

- 16 react on CTRL_C

- 17 helpful programs

- 18 See also

Hello world

The easiest way to get your feet wet with a programming language is to start with a program that simply outputs a trivial text, the so-called hello-world-example. Here it is for bash:

- create a file named hello in your home directory with the following content:

#!/bin/bash echo "Hello, world!"

- open a console, make the file executable:

chmod +x hello

- now you can execute your file like this:

./hello Hello, world!

- or like this:

bash hello Hello, world!

You see - the output of your shell program is the same as if you had entered the commands into a console.

calling commands

In your shell script you can call every command that you can call when opening a console:

echo "This is a directory listing, latest modified files at the bottom:" ls -ltr echo "Now calling a browser" firefox echo "Continuing with the script"

variables

input

To show you how to deal with variables, we will now write a script that asks for your name and greets you:

echo "what is your name? " read name echo "hello $name"

You see that the name is stored in a variable $name. Note the quotation marks " around "hello $name". By using these you say that you want variables to be replaced by their content. If you were to use apostrophes, the name would not be printed, but $name instead.

${}

The ${} operator stands for the variable, there is no difference if you write

echo "$name"

or

echo "${name}"

So what is the sense of this? Imagine you want to append a string, without any blank, to a variable:

echo "if I add the syllable owa to your name it will be ${name}owa"

common mistakes

Note that the variable is called $name, however the correct statement to read it from the keyboard is

read name

It is a common mistake to write

read $name

which means "read a string and store it into the variable whose name is stored in $name"

parameters

echo "Here are all parameters you called this script with: $@"

echo "Here is parameter 1: $1"

echo "Which parameter do you want to be shown? "

read number

args=("$@")

echo "${args[$number-1]}"

return codes

Every bash script can communicate with the rest of the system by

The return code is 0 if everything worked well. You can query it for the most recent command using $?:

bootstick@bootstick:~$ echo "hello world"; echo $? hello world 0 bootstick@bootstick:~$ echo "hello world">/proc/cmdline; echo $? bash: /proc/cmdline: Permission denied 1

In bash, true is 0 and false is any value but 0. There exist two commands, true and false that deliver true or false, respectively:

bootstick@bootstick:~$ true; echo $? 0 bootstick@bootstick:~$ false; echo $? 1

line feeds

In bash you can use line feeds or semicolons to separate commands. For example:

read name if [ $name = "Thorsten" ]; then echo "I know you"; fi

Instead of a semicolon you can write a line feed like this:

read name if [ $name = "Thorsten" ] then echo "I know you" fi

So we could put everything into one line and separate the commands by semicolons:

read name; if [ $name = "Thorsten" ]; then echo "I know you"; fi

If you want to insert a line feed where you do not need one, e.g. to make the code better readable, just put a backslash at the line's end to indicate it will continue:

read \

name

if [ $name = "Thorsten" ]

then \

echo "I know you"

fi

storing a command's output

To read a command's output into a variable use $(), backticks or piping.

$()

arch=$(uname -m) echo "Your system is a $arch system."

backticks

arch=`uname -m` echo "Your system is a $arch system."

piping

Piping is a very elegant concept in the Linux world. It allows you to take one command's output and use it as input for the next command. Now you can divide tasks into smaller tasks. For example instead of having a program counting all files in a directory you use one program (ls) to list all files in a directory and one program (wc) to count the lines:

ls | wc -l

You can also put the output into a variable, in this case $arch:

uname -m | while read arch; do echo "Your system is a $arch system."; done

comparison

The advantage of using backticks over $() is that backticks also work in the sh shell. The advantage of using $() over backticks is that you can cascade them. In the example below we use this possibility to get a list of all files installed with rpm on the system:

filelist=$(rpm -ql $(rpm -qa))

You can use the piping approach if you need to cascade in sh, but this is not focus of this bash tutorial.

common mistakes

Usually unexperienced programmers try something like

uname -m | read arch

which does not work. You must embed the read into a while loop.

conditions

The easiest form of a condition in bash is this if example:

echo "what is your name? " read name if [ $name = "Thorsten" ]; then echo "I know you"; fi

Now let's look closer at this, why does it work? Why is there a blank needed behind the [ sign? The answer is that [ is just an ordinary command in the shell. It delivers a return code for the expression that follows till the ] sign. To prove this we can write a script:

if true; then echo "the command following if true is being executed"; fi if false; then echo "this will not be shown"; fi

empty strings

An empty string evaluates to false inside the [ ] operators so it is possible to check if a string result is empty like this:

# result= # if [ $result ]; then echo success; fi # result=good # if [ $result ]; then echo success; fi success

arithmetic expressions

You can compare integer numbers like this:

echo "what is your age? " read age if (( $age >= 21 )); then echo "Let's talk about sex."; fi

However bash does not understand floating point numbers. To compare floating numbers you will use external programs such as bc:

$ if [ $(echo "2.1<2.2"|bc) = 1 ]; then echo "correct"; else echo "wrong"; fi correct $ if [ $(echo "2.1>2.2"|bc) = 1 ]; then echo "correct"; else echo "wrong"; fi wrong

not equal

To check if a variable is NOT equal to whatever, use !=:

if [ "$LANG" != "C" ]; then echo "please set your system lanugage to C"; fi

common mistakes

Common mistakes are:

- to forget the blank behind/before the [ or ] character

- to forget the blank behind/before the equal sign

- see what does "unary operator expected" mean

Redirections

To redirect the output of a command to a file you have to consider that there are two output streams in UNIX, stdout and stderr.

filling files

To create a file, probably the easiest way is to use cat. The following example writes text into README till a line occurs that only contains the string "EOF":

cat >README<<EOF This is line 1 This is line 2 This is the last line EOF

Afterwards, README will contain the 3 lines below the cat command and above the line with EOF.

loops

for loops

Here is an example for a for-loop. It makes a backup of all text files:

for i in *.txt; do cp $i $i.bak; done

The above command takes each .txt file in the current directory, stores it in the variable $i and copies it to $i.bak. So file.txt gets copied to file.txt.bat.

You can also use subsequent numbers as a for loop using the command seq like this:

for i in $(seq 1 1 3); do echo $i; done

while loops

$ while true; do read line; done

negations

You can negate a result with the ! operator. $? is the last command's return code:

# true # echo $? 0 # false # echo $? 1 # ! true # echo $? 1 # ! false # echo $? 0

So you get an endless loop out of:

while ! false; do echo hallo; done

The following code checks the file /tmp/success to contain "success". As long as this is not the case it continues checking:

while ! (grep "success" /tmp/success) do sleep 30 done

The following code checks if the file dblog.log exists. As long as this is not the case it tries to download it via ftp:

while ! (test -e dblog.log); do ftp -p ftp://user:password@server/tmp/dblog.log >/dev/null echo -en "." sleep 1 done

common mistakes

- bash is very picky regarding spaces. There MUST be a space after the ! if it means negation.

sending a process to the background

To send a process to the background, use the ampersand sign (&):

firefox & echo "Firefox has been started"

You see a newline is not needed after the &

forking a process

You can build a process chain using parantheses. This is useful if you want to have two instruction streams being executed in parallel:

(find -iname "helloworld.txt") & (sleep 5; echo "Timeout exceeded, killing process"; kill $!)

functions

To define a function in bash, use a non-keyword and append opening and closing parentheses. Here a function greet is defined and it prints "Hello, world!". Then it is called:

# greet()

{

echo "Hello, world"

}

# greet

If you hand over parameters you can greet any planet you like:

# greet()

{

echo "Hello, $1"

}

# greet Mars

Hello, Mars

# greet World

Hello, World

react on CTRL_C

The command trap allows you to trap CTRL_C keystrokes so your script will not be aborted

#!/bin/bash

trap shelltrap INT

shelltrap()

{

echo "You pressed CTRL_C, but I don't let you escape"

}

while true; do read line; done

- Note

- You can still pause your script by pressing CTRL_Z, send it to the background and kill it there. To catch CTRL_Z, replace INT by TSTP in the above example. To get an overview of all signals that you might be able to trap, open a console and enter

kill -l

helpful programs

awk: read a specific column

awk is a program that is installed on almost all Linux distributions. It is a good helper for text stream processing. It can extract columns from a text. Let's imagine you want to use the program vmstat to find out how high the CPU user load was. Here is the output from vmstat:

|

VmStat |

We see the user load is in colum 13, and we only want to print this column. We do it with the following command:

vmstat 5 | awk '{print $13}'

This will print a line from vmstat all 5 seconds and only write the column 13. It looks like this:

# vmstat 5 | awk '{print $13}'

us

1

1

0

1

To store the CPU user load into a variable we use

load=$(vmstat 1 2 | tail -n 1 | awk '{print $13}')

What happens here? First vmstat outputs some data in its first line. The data about CPU load can only be rubbish because it did not have any time to measure it. So we let it output 2 lines and wait 1 second between them ( => vmstat 1 2 ). From this command we only read the last line ( => tail -n 1 ). From this line we only print column 13 ( => awk '{print $13}' ). This output is stored into the variable $load ( => load=$(...) ).

grep: search a string

grep is a program that is installed on almost all Linux distributions. It is a good helper for text stream processing. It can extract lines that contain a string or match a regex pattern. Let's imagine you want all external links from www.linuxintro.org's main page:

wget -O linuxintro.txt http://www.linuxintro.org grep "http:" linuxintro.txt

sed: replace a string

sed is a program that is installed on almost all Linux distributions. It is a good helper for text stream processing. It can replace a string by another one. Let's imagine you want to print your distribution's name, but lsd_release outputs too much:

# lsb_release -d Description: openSUSE 12.1 (x86_64)

You want to remove this string "Description" so you replace it by nothing:

lsb_release -d | sed "s/Description:\t//" openSUSE 12.1 (x86_64)

Once you understand regular expressions you can use sed with them:

- to replace protocol names for a given port (in this case 3200) in /etc/services:

sed -ri "s/.{16}3200/sapdp00 3200/" /etc/services

- if you have an apache web server here's how you get the latest websites that have been requested:

cat /var/log/apache2/access_log | sed ";.*\(GET [^\"]*\).*;\1;"

tr: replace linebreaks

sed is a program that is installed on almost all Linux distributions. It is a good helper for text stream processing. It can replace a character by another one, even over line breaks. For example here is how you remove all empty lines from your processor information:

# cat /proc/cpuinfo | while read a; do ar=$(echo -n $a|tr '\n' ';') if [ "$ar" <> ";" ]; then echo "$ar"; fi; done

wc: count

With the command wc you can count words, characters and lines. wc -l counts lines. For example to find out how many semicolons are in a line, use the following statement:

while read line do echo "$line" | tr '\n' ' ' | sed "s/;/\n/g" | wc -l done

It lets you input a line of text, counts the semicolons in it and outputs the number.

How does it do this?

It reads lines from your keyboard (while read line). It outputs the line (echo "$line"), but it does not output it in the console. The pipe (|) redirects the output to the input stream of the command tr. The command tr replaces the ENTER ('\ ') by a space (' '). The pipe (|) redirects the output to the input stream of sed. sed substitutes ("s/) the semicolon (;) by (/) a linefeed (\ ), globally (/g"). The pipe redirects the output to the input stream of the wc -l command that outputs the count of lines.

dialog: create dialogs

Dialog is a command that helps you creating dialogs in the shell. The answers given by the user are send to stderr and/or influence the command's return code. For example if you run this script:

#!/bin/bash if (dialog --title "Message" --yesno "Are you having fun?" 6 25) then echo "glad you have fun" else echo "sad you don't have fun" fi

It will display this dialog:

This has been taken from http://www.linuxjournal.com/article/2807. Read there for more info.

See also

- bash

- shell

- scripting

- bash operators

- http://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Bash_Shell_Scripting

- http://ryanstutorials.net/linuxtutorial/scripting.php

- http://wiki.linuxquestions.org/wiki/Bash_tips

- http://wiki.linuxquestions.org/wiki/Bash

- http://linuxconfig.org/Bash_scripting_Tutorial

- http://steve-parker.org/sh/intro.shtml

- http://mywiki.wooledge.org/BashFAQ

- http://mywiki.wooledge.org/BashPitfalls